Estimated reading time: 9 minute(s)

OK, I admit. That’s just a fun, “grab-your-attention” kind of headline.

OK, I admit. That’s just a fun, “grab-your-attention” kind of headline.

But it’s not far from the real truth. At least for many of us U. S. Americans.

The first amendment protection of free speech, and more specifically the part about freedom of religion was the central part of an interesting discussion the other day.

It began innocently enough with me overhearing a conversation about how the Constitution might be applied in a case regarding State versus Federal powers. The Constitution was written to limit the Federal government’s power over the People, and also over the individual States’ governments.

That’s not very well understood today, by my reckoning.

Back to the scenario that was unfolding. One party was trying to suppose what outlandish bill might be passed by a state legislation, which, in context might have had something to do with religious activities, perhaps in schools. The other party suggested that perhaps the bill might try to instate mandatory school prayer. At this, the first party scoffed, rigidly stating that the Constitution would clearly prohibit such a thing. To which the second party responded—though backing off, slightly—that it might be possible at the state level. Party One maintained his unyielding stance that it was a definite violation of the Constitution to require prayer in a public school.

So, I thought, Actually, the second guy is kind of right—though, no state would ever require such a thing—that the states are free to pass such bills and laws, if they so choose. The federal government can not interfere with this if a state would choose to do so.

This is where I decided to join the conversation.

At first, Party One stuck to the, uh, “party line” of zero allowance for anything which could be seen as religious being mandated by the states, because the Constitution prohibits such a possibility. I maintained that while I thought that was an awful idea that would never even be attempted, it was not unconstitutional.

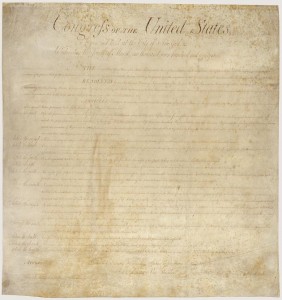

Let’s examine the First Amendment:

Amendment I

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

That’s it. Congress shall make no law regarding the establishment of religion, or prohibit the free exercise thereof. The only other mention of religion in the Constitution is that there would be no “religious test” for becoming a congressman.

Today we interpret that one sentence above to mean that any public institution, office, official, or representative—any entity with any connection to any level of government—can not in any way espouse, promote, endorse, or engage in any activity which might be construed as “religious”.

But that’s not what it says at all, really.

I’m getting off track here. We can revisit the First Amendment in tomorrow’s post. Let’s stick to the topic: Federal vs. State powers.

Specifically, can the Federal government overrule a State government’s law or proclamation, or any such legislation intended for its citizens?

Thomas Jefferson is an interesting example here. When he was Governor of the State of Virginia, he called for a day of thanksgiving and prayer on December 9, 1779, saying:

“I do therefore by authority from the General Assembly issue this my proclamation, hereby appointing Thursday the 9th of December next, a day of publick and solemn Thanksgiving and Prayer to Almighty God, earnestly recommending that all the good people of this commonwealth, to set apart the day for those said purposes… (signed) Thomas Jefferson” [ref]

But as the third President of the United States, he said the following on the same (similar) subject:

“I consider the government of the United States as interdicted by the Constitution from intermeddling with religious institutions, their doctrines, discipline, or exercises…Certainly no power to prescribe any religious exercise, or to assume authority in religious discipline, has been delegated to the general government. …But it is only proposed that I should recommend, not prescribe a day of fasting and prayer. That is, that I should indirectly assume to the United States an authority over religious exercises, which the Constitution has directly precluded them from…civil powers alone have been given to the President of the United States and no authority to direct the religious exercises of his constituents.” [ref]

Fascinating, huh? Doesn’t this seem to be two different ideas? Was Jefferson under duress when, as Governor, he wrote and signed that very religious-sounding proclamation of a day of Thanksgiving and Prayer for his state (the Commonwealth of Virginia)? Or did he just change his mind? I should think not the latter because he was the author of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom, which is one of the three lifetime achievements he wanted inscribed on his gravestone at Monticello. (A list which conspicuously does not include being President of the United States.)

Well, as it turns out, that’s not all there was to it.

I dug a bit more, and read a bit more, and found the full text for that response to Samuel Miller, quoted incompletely on the Monticello website (and above). It would seem that context would give us a much more clear picture of why Mr. Jefferson did not think it was his place (nor that of the “General Government”) to be “intermeddling with religious institutions”.

I know this is a bit long already, but I’d really like for you to read the following in its entirety.

Washington, Jan. 23, 08

Sir,—I have duly received your favor of the 18th and am thankful to you for having written it, because it is more agreeable to prevent than to refuse what I do not think myself authorized to comply with. I consider the government of the US. as interdicted by the Constitution from intermeddling with religious institutions, their doctrines, discipline, or exercises. This results not only from the provision that no law shall be made respecting the establishment, or free exercise, of religion, but from that also which reserves to the states the powers not delegated to the U. S. Certainly no power to prescribe any religious exercise, or to assume authority in religious discipline, has been delegated to the general government. It must then rest with the states, as far as it can be in any human authority. But it is only proposed that I should recommend, not prescribe a day of fasting & prayer. That is, that I should indirectly assume to the U. S. an authority over religious exercises which the Constitution has directly precluded them from. It must be meant too that this recommendation is to carry some authority, and to be sanctioned by some penalty on those who disregard it; not indeed of fine and imprisonment, but of some degree of proscription perhaps in public opinion. And does the change in the nature of the penalty make the recommendation the less a law of conduct for those to whom it is directed? I do not believe it is for the interest of religion to invite the civil magistrate to direct it’s exercises, it’s discipline, or it’s doctrines; nor of the religious societies that the general government should be invested with the power of effecting any uniformity of time or matter among them. Fasting & prayer are religious exercises. The enjoining them an act of discipline. Every religious society has a right to determine for itself the times for these exercises, & the objects proper for them, according to their own particular tenets; and this right can never be safer than in their own hands, where the constitution has deposited it.

I am aware that the practice of my predecessors may be quoted. But I have ever believed that the example of state executives led to the assumption of that authority by the general government, without due examination, which would have discovered that what might be a right in a state government, was a violation of that right when assumed by another. Be this as it may, every one must act according to the dictates of his own reason, & mine tells me that civil powers alone have been given to the President of the US. and no authority to direct the religious exercises of his constituents.

I again express my satisfaction that you have been so good as to give me an opportunity of explaining myself in a private letter, in which I could give my reasons more in detail than might have been done in a public answer: and I pray you to accept the assurances of my high esteem & respect. (Emphasis mine.)

Jefferson very clearly stated that (1) religious freedom, and the power to hold that, belonged with the people (and religious institutions) and the Constitution “deposited it” there, (2) that states “might” have the right to declare a public day of thanksgiving and prayer, but that (3) the general (federal) government, most certainly does not. So says the Constitution. (As well as one of the most ardent supporters of religious liberty.)

The main point for this first installment of Constitutionally Speaking is that the Constitution does not grant the Federal government supreme power. That is not and never was the intent. The intent of the Constitutional Convention of 1787 was to grant some limited power to a federal governement that represented all the individual States as the United States of America. It was a compact created by the People, and the authority remained with the People and their State governments and representatives.

We have lost that today, in my opinion. It seems more that we view the power residing in Washington, and doled out as those in charge from there see fit.

That’s not how our government is supposed to function, however:

James Madison said as much in Federalist No. 45:

“The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite.” [ref]

That does not sound like a government over the People, does it?

No. And that’s where we came from, and who we still are.

It’s essential that we have a proper understanding of our founding documents, but too often we just think we do. It is more common to find that someone has a second- or third-hand understanding of American governement, learned through a long-ago high school history course, or perhaps (and far worse) learned from some partisan commentator on talk radio or the internet. (And even worse than that… on TV!)

Original sources are the only way we can truly know history. Thankfully, we have those original sources very readily available to us. It may take more time and effort, but it’s definitely worth it, and will preserve the freedoms we have going forward, generation to generation.

Tomorrow I want to explore the First Amendment more in-depth. I hope you’ll join me! And please do add your thoughts in the comments below.

AND, lastly, and paramount: please find, purchase, own, and read the original documents! (Many of them are free in digital version!)

See you here tomorrow!

[…] to the point of yesterday’s initial question: while a state would almost certainly never propose a bill mandating prayer in schools, a local, […]

[…] central point to the current Constitutionally Speaking series (I, II, III) has been to understand the original intent of the Constitution. When it was written, the […]