Estimated reading time: 8 minute(s)

If you are a fan of history, and perhaps also an American citizen—both of which I am—then I hope you’ve enjoyed this look at our Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, as seen through the eyes, words, and actions of the people who constructed it. It’s very interesting to see where we’ve come from, how it began, and even the direction we are going.

If you are a fan of history, and perhaps also an American citizen—both of which I am—then I hope you’ve enjoyed this look at our Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, as seen through the eyes, words, and actions of the people who constructed it. It’s very interesting to see where we’ve come from, how it began, and even the direction we are going.

I am certainly no authority on this subject, but I’ve spent a good amount of time (even as I wrote these articles) studying original sources and commentaries upon those. I would definitely encourage you to do the same if you are made curious by what I’ve written, or find that you wholeheartedly disagree!

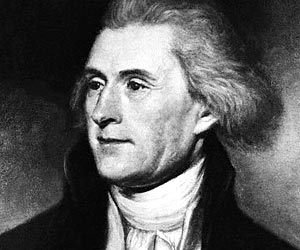

Regarding the pursuit of truth, even in regards to theology and religion, Thomas Jefferson advised:

“Fix reason firmly in her seat, and call to her tribunal every fact, every opinion. Question with boldness even the existence of a god; because, if there be one, he must more approve the homage of reason, than that of blindfolded fear.”

It’s up to each of us to learn what we believe, and why we believe it. And never be afraid to question it.

In this series, we’ve looked at the initial question—whether or not the federal government has the authority to limit what laws an individual State can or can not pass—as well, we have considered whether the Bill of Rights grants rights, or protects them.

And now we come to the conclusion.

The central point to the current Constitutionally Speaking series (I, II, III) has been to understand the original intent of the Constitution. When it was written, the framers hoped to grant very limited powers to the federal government, while the states would each retain “numerous and indefinite” powers.

James Madison said as much in Federalist No. 45:

“The powers delegated by the proposed Constitution to the federal government are few and defined. Those which are to remain in the State governments are numerous and indefinite.” [ref]

In the first part of this series, I quoted Thomas Jefferson several times as I feel that he was a great example of this strong conviction that the Federal government should not have powers over the States, other than any specifically granted to it. Jefferson was an anti-federalist: he was opposed to a strong central government. The Federalists were the framers of the Constitution (thus the Federalist Papers, explaining the reasoning behind the Constitution) but one of the hallmarks of the document was that all members of the Constitutional Convention made every effort to come to complete agreement—Federalist and Anti-Federalist alike; consensus, rather than just a majority vote. Thus was born a limited, central (Federal, general) government, designed to function as the representative of all the states in four areas: common defense, preservation of peace (domestic and foreign), regulation of domestic (interstate) and foreign commerce, and diplomacy with other nations. [ref]

In this last edition of this series, I have one last Jefferson quote for you. This one is from The Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, when Kentucky successfully brought a grievance against the General Government for overstepping its authority:

That the several States composing, the United States of America, are not united on the principle of unlimited submission to their general government; but that, by a compact under the style and title of a Constitution for the United States, and of amendments thereto, they constituted a general government for special purposes — delegated to that government certain definite powers, reserving, each State to itself, the residuary mass of right to their own self-government; and that whensoever the general government assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force: that to this compact each State acceded as a State, and is an integral part, its co-States forming, as to itself, the other party: that the government created by this compact was not made the exclusive or final judge of the extent of the powers delegated to itself; since that would have made its discretion, and not the Constitution, the measure of its powers; but that, as in all other cases of compact among powers having no common judge, each party has an equal right to judge for itself, as well of infractions as of the mode and measure of redress. [ref]

And all of that is to say: the States, and the People, still hold ultimate, final, and also primary power.

The Constitution was written to bring together several autonomous states under one “general government”. It’s purpose was to spell out the compact between those states, and those people, to be one entity—one people.

Somewhere along the way (many places, actually) we moved from a place where we were many states joined as one (e pluribis unum?) to one very large “state”, commanding and governing from the central head: Washington.

That’s not what we were designed to be. The Constitution allows for, or more accurately, attempts to preserve a government closer to the people. Local and state governments, comprised of neighbors. True representatives. (We are not a democracy. The United States federal government is a federal republic. It is a group of representatives from other states/entities.)

This was fundamentally lost during the Civil War. It was, in fact, the primary cause and reason for the Civil War. The south, as wrong as they were about slavery, believed strongly in states rights and autonomy. The north believed more closely what the Federalists believed: a strong central government was essential to a strong Union. The north was victorious (which was good for preserving our union, and of course for finally abolishing slavery) and thus was cemented the United States of America in its current form.

Prior the the Civil War, the country was refered to in the plural: “The United States are…” Following the War, that phrase became, “The United States is…” [ref] Hear the difference? We are no longer one from many, we are just one.

When one examines the way our country was first established, and the intended separation of powers, it’s rather fascinating to see how much we’ve changed over time. It seems now rather commonplace to think that Washington or the federal government is our supreme authority. As we’ve seen, power was originally supposed to be remain more with the state and local governments—and of course, the People. This allows for a much more diverse—and free?—people overall.

But, as the saying goes, “Give an inch, and they’ll take a mile.”

When we first saw the need as a nation to cede some of our autonomy to a central government in order to exist and survive as a society or a nation, we allowed for the possibility of ceding more and more power to that created entity. Our Constitution provides amazing checks and balances, and separations of power, and multiple devices for ensuring, as best as possible, that the power remains first with the People. And yet today, the People generally operate as though the government has primary power and authority, which it then grants to the People (generally bypassing the States entirely).

This has occurred, in my opinion, simply as a result of that first “foot in the door” of drafting and ratifying the Constitution—great as that document may be. But it has progressed thanks to the desire within Man’s spirit to be led, to have a King. (See here, and here for more on that.)

Also helping us toward a view of our federal government as the more centralized authority are several Supreme Court decisions as well as constitutional amendments throughout the generations.

The Supremacy Clause (Article VI, Clause 2) of the Constitution has often been interpreted to grant primacy to Federal law (power) when any conflict with State law might exist. The First Amendment has often triggered the use of this Clause to determine where the authority lies, as far back as cases in 1803. Subsequent cases and rulings [example], as well as the Fourteenth Amendment, followed by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal [ref], have all led us to a place where we see the Federal government as supreme, and continue to move it towards greater power, primacy and supremacy.

At some point we might discover that we have ceded too much power.

For now, we Americans are definitely one of the most free people and civilizations of all time. Our Constitution is still the basis for preserving and protecting that freedom. We are a people governed by Rule of Law, not a privileged class or other type of nobility. This ensures the opportunity of fairness and equal justice for all.

Many attempts are made to undermine that. (Lust for power is a strong force, as is the desire for comfort and safety.) Benjamin Franklin was asked, “Well Doctor what have we got—a republic or a monarchy?” His reply? “A republic, if you can keep it.” He is also credited with saying, “They who can give up essential liberty to obtain a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety.”

Freedom is our God-given right; unalienable. However, to coexist with others as a nation, as a republic—the United States of America—we must work to preserve that freedom. Knowledge of the original intent is essential, as well as a foundation in the understanding that neither we nor any government, whether of our own construct or forced upon us are ultimately in authority over us. God the Creator is our supreme authority, and one reason that our republic has survived is that He and the ways of his Kingdom were central to the worldview of the Framers.

But that’s for another series… 🙂

I encourage you to find the original sources mentioned or linked here. Own a copy if possible. Read, understand, and pass along.

And in that way, you can be part of perserving our liberties, from generation to generation.